Digging Into Diversity: International Women's Day 2024

Lead Author:

Georgie Taylor (Senior Analyst – State of Play)

Contributing Authors:

Lisa Harwood (Director – State of Play)

Sarah Boyatzis (Principal – Slate Advisory)

Kelly Williams (Business Operations Administrator – Slate Advisory)

“Change doesn’t occur unless the discomfort with the current position exceeds the difficulty of the first steps.”

– John de Vries

“Women who are as fortunate to sit in the sorts of roles that I do, we need to make sure that we’re creating change, not just adapting and making it work for ourselves, but actually creating change.”

– Michelle Carey

Within the mining industry, as with many industries more broadly, there is an increasing level of discussion surrounding diversity. Diversity is not a box-ticking exercise, nor is it a purely altruistic pursuit – establishing and enabling diversity within an organisation is a powerful strategic tool for improving innovation, team resilience and performance.[1]

Acknowledging that diversity of thought can advance the competitive advantage of a business is an easy first step, but it’s more difficult to achieve genuine diversity of thought without an embedded culture that includes a true variety of people. Societal diversity is multifaceted, encompassing myriad aspects of identity including gender, ethnicity, culture, sexual orientation, age, experience, education level, socioeconomic status, and many more.

In celebration of International Women’s Day, we interviewed 15 leaders from the mining industry and beyond, boasting a collective ~350 years of professional experience. They shared invaluable insights into diversity in the workplace, offering their perspectives to inspire change. This piece intends to showcase the resilience of individuals to overcome and dismantle barriers for those who follow, and the remarkable impact that diversity offers. It also intends to spark a vital conversation about the “people problems” faced by mining organisations, to encourage leadership-based solutions benefitting both organisations and their people. We invite you to read it with an open mind, to discuss it with your friends and colleagues, and to reach out to us with your thoughts.

Who we spoke to

Our panel of 15 interviewees are individuals, and their perspectives do not necessarily represent those of the broader groups to which they belong, be it gender, cultural background, or employer.

The dirty truth

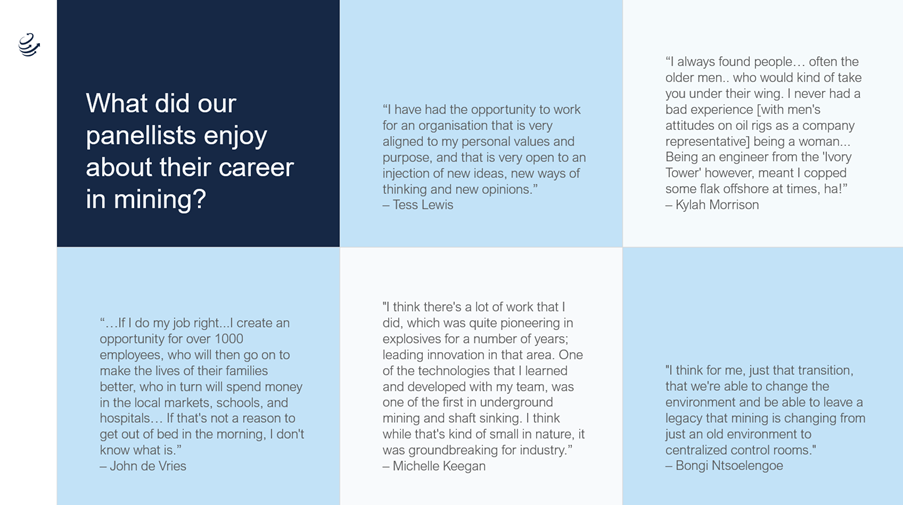

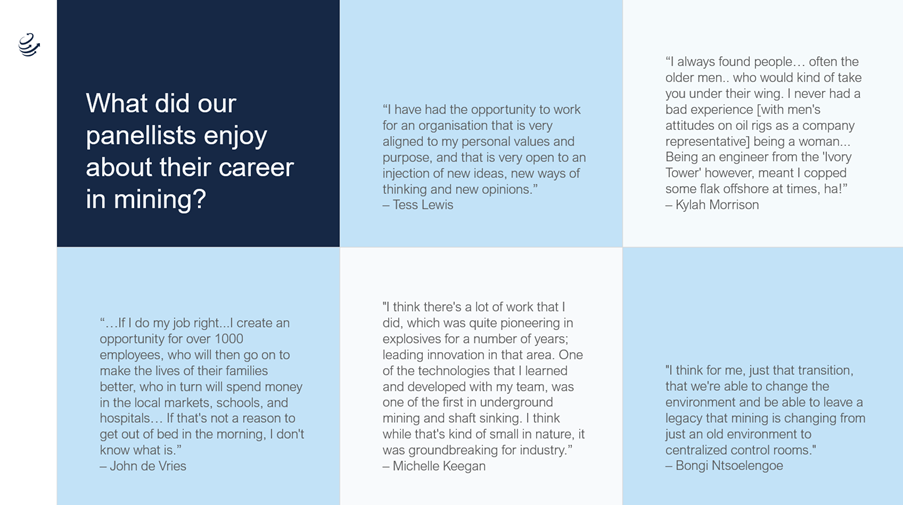

Even today, mining is often considered a traditionally masculine industry. With men composing over 78% of the Australian mining workforce, and popular advertising tropes of big trucks, dirt roads, and high-vis uniforms, it’s not hard to see why this perception persists. In reality, mining is a vast and complex industry comprising a variety of roles, and a variety of people – but these tales aren’t always told. Our panel spoke candidly to us about their career experiences, shedding light on the rarely heard stories of women in mining over the last forty years. Despite persistent systemic issues, our panel unanimously advocated for a career in mining, due to the challenging problem-solving, the interesting people, the opportunities to travel, and the chance to make a tangible difference to communities.

“I worked on a mine site in Tanzania, where I was surprised at the response, I had assumed that there would be concerns about a female GM/COO but in fact they embraced having a ‘Mama’ leading them. There were other areas like going underground where I was treated differently to other women: ‘it’s not that she’s a woman, because that would break our thinking about stuff… It’s that she’s a Michelle.’”

– Michelle Ash

“It was said to me: “What are you doing here? You should be at home making babies.” He literally said that, those were his words. I’ve always been a bit cheeky, so, I kind of paused and I was like “well, I should ask you then why you’re not on the couch having a beer!”

– Simone Naicker

When some of our panellists started their careers, it was considered bad luck for a woman to go underground.[2] Beyond the realm of superstition, we also heard about on-site working obstacles, ranging from a lack of women’s accommodation and bathroom facilities to secure transport when travelling to remote regions alone (many of our panellists faced these issues firsthand as students). While some of these systemic barriers have since been addressed, the underrepresentation of women on-site in mining has persisted. In 2022, women’s participation in FIFO and DIDO roles in Australia was around 27% of the workforce, and 41% of women in these roles reported poor perceptions of workplace diversity and inclusivity.[3]

Back in metropolitan offices, the work tends to be cleaner, less physical, and more suited to those with caregiving obligations. Despite this (or perhaps because the difficulties are more covert), corporate mining jobs are also challenging places for women to work – and the more successful the woman, the more gendered the challenges appear to be. Australian statistics show that the representation of women in mining in 2022-2023 remained consistent (23-25%) for most office-based roles but declined sharply at the most senior levels (8% of Australian mining CEOs are women, compared to 22% across all industries).[4]

“I think there are aspects of being a woman in the C-suite that are as hard or harder [as being out on the field]. I think that’s been of most surprise to me.”

– Michelle Carey

“When I first entered the industry, I was perceived as enthusiastic and young, and so the senior managers were so willing to share their knowledge…

– Diane Dowdell

As soon as you transition from that role into the supervisory role, your job is to potentially challenge their views about how things should be progressed. You go from being this sponge, that sucks in knowledge to ‘Why are you being so difficult? If you were never difficult previously, why are you now being so difficult?’”

“I was told not to be soft, don’t let your subordinates see your emotional side of you. You know, you always need to have this macho side; leaders don’t cry…”

– Bongi Ntsoelengoe

Some of our panellists spoke about the difficulties they had encountered in their corporate careers, including being repeatedly asked to fetch coffee or take minutes in their own meetings, hearing sexist jokes, having others taking credit for their work, or an expectation from male colleagues to “behave like their wives”. There was also an overarching sense of isolation and lack of like-minded support, a consequence of often being the lone woman in a room. Multiple panellists highlighted a transition in their peers’ attitudes towards them as they progressed into positions of increased power.

No equity without enablement

“…we can bring matters to the fore around having specific facilities because we are hiring people that are adequately qualified to do that work. I’m a woman and I’m a truck driver and I’ve been hired, and I don’t have a bathroom. The fact that I’m raising that I don’t have a bathroom, it has nothing to do with the fact that I’m a female. Why can’t we have unisex toilets? So instead of labelling that toilet as a male toilet, let’s just have unisex toilets, then all of us can use the bathroom.”

– Bongi Ntsoelengoe

A few panellists explicitly highlighted that these challenges should not be pigeonholed as gender-based issues, a framing that can set companies up to disregard them as fringe problems rather than issues central to business operations.[5] In reality, all of these issues are examples of organisations failing to provide an environment that enables an employee to do their best work, regardless of their identity traits. Conversely, several panellists highlighted their supportive team environment as the reason they were able to perform so strongly in their roles (notably, these individuals have been widely celebrated for their achievements).[6]

“We have to talk about culture as well… culture is one of the hardest things to change, because much of it influences on a subconscious level. To get this deep understanding and then envision and implement change, a buy-in and drive from the top are extremely important, to create the momentum which eventually will change the whole company.”

– Wolfram Sommer

“As a leader, you have to find a way to be comfortable with vulnerability, share a little bit more… that is actually part of the job description”

– Tijana LaBianca

“You might think, ‘Oh, someone’s going to challenge me all the time’, but that’s necessary to push boundaries… It’s about recognising that as a boss, you don’t know everything, and you hire smart people to advise you. You must listen to them! At the same time, encourage them to seek diverse opinions, as it’s easy to fall into groupthink, especially after past successes.”

– John de Vries

Managing diverse teams is challenging – and that’s exactly the point. It’s easy to lead a homogenous group, willing to conform without question, but leading a diverse group with multiple (and sometimes conflicting) ideas, experiences and requirements calls for mature human-centred leadership skills like humility, empathy, facilitation, and open-mindedness. Strong leaders actively listen to their teams – they provide space for them to voice their thoughts, and they encourage them to also think outside the box. They acknowledge that as a leader, their job is not to know everything, but rather, to learn from their team and enable them to do their best work. And most importantly, true leaders don’t find excuses for not leaning into hard conversations; it’s their job to be actively engaged.

“I’ve learned that I only have a sufficiently diverse team when they challenge me or make me feel uncomfortable.”

– Michelle Ash

On improving workplace diversity: “…You’re going to get it wrong. If you [men and women] feel like you’ve got a safe environment where you can ask the questions that are awkward, and not politically correct, and feel like you are supported in that space to better understand what is appropriate, and what’s not appropriate… that’s where we really make inroads with positive change.”

– Kylah Morrison

Our panel agreed that an effective leader empowers their teams through flexibility. An effective leader acknowledges that inclusion means everyone might want or need something different from the workplace and recognises that the established systems may not have been designed with the modern workforce’s needs in mind. Moreover, they understand that diversity without inclusion can lead to isolating workplace experiences, or even a “crash and burn” system that reinforces negative stereotypes. Adjusting the operating model to address inclusion challenges can be daunting, yet a more diverse workplace with greater emphasis on human-centered leadership offers equitable benefits to both men and women. Normalising parental leave, carer’s leave, and working flexibly not only advances gender equality but also enhances work-life balance and productivity for all employees. Building a culture that prioritises psychological safety and mental well-being at a broader scale fosters trust and innovation, improving retention, performance, and ultimately, the success of the organisation.

A pervasive people problem – with a purple people solution?

State of Play Mining Industry Survey 2023: 35% of our 720 respondents identified as female.

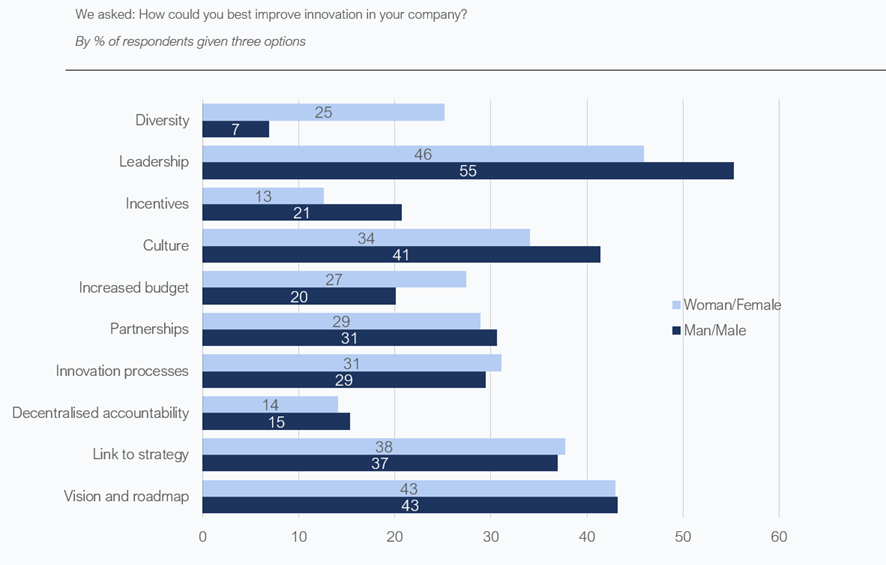

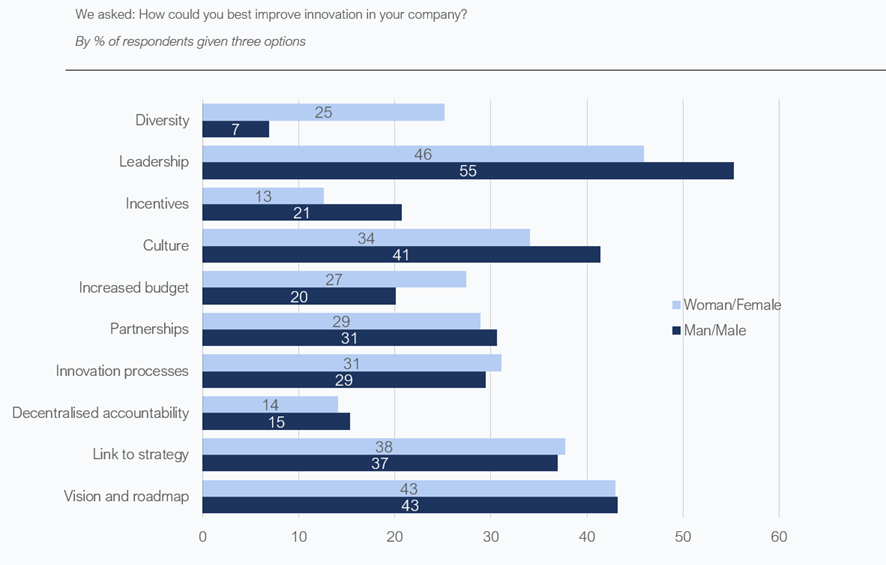

Discourse on diversity in the workplace is crucial for driving change, however, it’s difficult to understand and address the everyday realities if you’ve never felt out of place at work or experienced professional barriers due to your identity. The juxtaposition of experience between those who have always belonged to a single ecosystem that aligns with their identity, versus those who have been a part of, or encountered, multiple conflicting systems, can manifest as a serious disconnect within teams. It’s the role of leadership to foster an open environment where people feel comfortable talking about their experiences and are listened to when they discuss their differences.

“Sometimes I’m sitting in a meeting, there’s three women in the meeting, and one of the guys is asked to describe the experience of women in mining. Does that make sense?”

– Michelle Ash

“Anyone who is in a minority group… can see the value of diversity, because they’ve experienced what it’s like when their voice hasn’t been heard… If you don’t know another way of operating, it makes sense that you’re not going to see the value of change.”

– Kylah Morrison

“I think there are these unconscious biases and things that people aren’t really doing on purpose. So, when you pointed it [non-inclusive behaviours] out, then they would be more likely to have that in mind next time, if they can’t change it this time.”

– Celia Merzbacher

Multiple members of our panel categorised “people problems” as a critical issue in mining – one panellist described the industry as a “three-legged chair”, with fundamental pillars of technical, financial, and social capabilities. Remove any one of these, and the whole thing topples over. This sentiment is supported by independent data – our 2023 Mining Industry Survey respondents selected “people” as their leading area of operational competitive advantage. Startlingly though, both our oldest and youngest interviewees highlighted that engineering graduates are often unprepared to navigate workplace dynamics effectively as they don’t necessarily have training in the people skills required to work efficiently within and across teams.

Ironically, our panel also agreed that women often demonstrate a greater aptitude for navigating social issues. So, by failing to train emerging engineers in people skills, and simultaneously failing to hire people with a natural affinity for these skills, the mining industry’s fundamental social pillar is twice weakened. Ensuring social capabilities are appreciated and developed is an important enabler for both the success of a mining company and the success of its diversity strategy.

“I think for me, I guess it would be more about inclusion… it’s easy to have the diverse person on your team, but it’s about how to make them feel included, and their voice heard, and put them in the position that they can make a difference.”

– Danielle Nardini

“I think half of our problems are people problems. The machinery works, we just need to maintain it and optimise the process and check efficiencies, and I mean, the technical process is there. And it’s just that the people stuff is often poorly managed. That’s what we need to solve.”

– Simone Naicker

“It’s not just the leadership, people that are at the top to enforce it, but also within our environment. We need to encourage people to start recognising humanity in people.”

– Bongi Ntsoelengoe

Tapping the deep end of the talent vein

It’s clear that companies need to hire the best people for the job, but right now, that’s not necessarily what happens. The current system is rife with unconscious bias – even the most well-intentioned manager may be more likely to appoint a candidate to a role if they can see their younger self in them. Given the vast majority of mining managers are men, this situation creates a reinforcing feedback loop that is difficult to correct (and that’s assuming there’s motivation to correct it in the first place). Layer that on top of the evidence showing women may be less attracted to join the industry,[1] unnecessary barriers to entry on job advertisements (it is well known that women tend not to apply unless they meet every requirement, so do you really need your manager to have an engineering degree?), and a limited number of successful role models who represent them, and it’s no wonder why mining organisations are struggling to assemble gender-diverse teams in an increasingly competitive environment. And this issue isn’t just robbing organisations of talented women – it’s also robbing them of talented men who have no appetite for groupthink or monoculture.

“I’ve just always gone looking for capable people. I’ve never thought about it through a lens…If I reflect on it, I think diversity was one way to get capability in a tough environment.”

– Graeme Stanway

“Now when you go to organisations and there isn’t diversity, you sort of go, right… where are the different opinions? I would not actually take on a job in a company which didn’t have a diverse leadership team”

– David Ruddell

To quota, to target, or to KPI?

When asked about their position on affirmative action, there were diverging views depending on whether quotas, targets or KPIs were being discussed. With a job quota, the focus is on the percentage of jobs that must be given to a particular group of individuals (for example, women). Some of our panellists were strong supporters of quotas, believing that they were the only way to ensure that changes to the hiring status quo would happen quickly. Most, however, supported hiring targets, which are longer-term goals to recruit people from different backgrounds. Targets force hiring managers to think differently about candidates they haven’t previously considered, e.g., graduates from non-traditional mining degrees (female or otherwise). Unlike quotas, they are considered to be a performance metric, similar to a KPI, and can serve as a measure of progress.

For some panellists though, even diversity targets were offensive. There are widely reported cases of peer backlash or imposter syndrome by employees thought to be hired under a target, regardless of whether the person has the credible skills to be in that role. Some people have also had difficult and frustrating experiences, working with incompetent people who were hired under targets. There are important contextual overlays to this issue – for example, South Africa’s Employment Equity Amendment (which implements racial targets and quotas) has been particularly controversial.

Regardless of the metric used, anything implemented must be backed up by a set of hiring and enablement practices. Like any change management piece, the end goal isn’t announcing the program or project, it’s how that is rolled out and embedded within the organisation.

The question then remains: How do we ensure we’re actually hiring the right person for the job? And if we are going to hire a wider variety of people, then where are we going to find them?

“Placing non-traditional profiles in significant leadership roles shouldn’t be done haphazardly or just to fill some quota: it must be accompanied by an approach that fosters a culture of inclusion and respect, and that tackles the inherent bias and discrimination that exists in non-diverse companies and industries (such as mining)…

– Tess Lewis

Targets are not lowering the competence for a job, they are just giving access to competent professionals with a different profile who would have been pushed aside because of the biases we, unconsciously, all have. Without targets and metrics to measure current status and monitor progress, any diversity and inclusion efforts will always amount to shooting in the dark.”

“Ultimately, that’s really what targets are about. They are actually about forcing people to think differently in who they recruit and where they recruit from. You have to be innovative, just in going to find people.”

– Michelle Keegan

“Nobody wants to be in an environment because quotas say so. I want to be there because I have the merit to be there. And that’s why I am not a supporter of ‘Women in Mining’. I don’t subscribe to women in mining because it’s people in mining. Why does it matter whether I’m a female or male?”

– Bongi Ntsoelengoe

Exploration is key: finding the next generation of miners

At the heart of its diversity challenges, mining has a well-known perception problem. Our panel highlighted this as the primary obstacle to attracting diverse teams to the industry – and while images of big trucks, dirt roads, and high-vis uniforms persist, this perception will perpetuate. The next generation of workers and leaders have seen those images, and they’re just not interested.

What if the range of roles that existed within the mining industry were advertised, rather than the stereotype we see so often in media? What if, as well as clipboards and hard hats, we spotlighted the people who travel the world to negotiate with local stakeholders, who pioneer ground-breaking technologies to make a virtual mine twin, or who facilitate ambitious studies and programs to better protect the biodiversity and community around mine sites?

What if the mining industry showcased the allure of fulfilling, high-impact, and socially oriented work that appeals to emerging generations, alongside the personal opportunities such as pursuing advanced degrees, embarking on global adventures, working with interesting people, and enjoying great benefits – a trifecta of global, local and personal incentives to attract a diverse and modern talent pool.

What if we reminded everyone: mining isn’t just one thing – it touches almost everything in society. Mining isn’t just one job – it’s an entire ecosystem, where almost any talent can be harnessed and rewarded. And mining isn’t just for one type of person – it’s for everyone, and it needs everyone in order to address the challenges of our rapidly changing world.

Thank you to our exceptional panel of experts, who generously volunteered their time, stories, and insights for this piece. To stay engaged with this issue, we suggest reaching out to a local mining group – here in Perth, we’re fans of Women in Mining Western Australia (WIMWA).

This is just the beginning of a rich and complex conversation – look out for more from State of Play soon. In the meantime, check out our 2023 Mining Industry Survey reports for more insights from State of Play data – launching mid-March 2024. You can sign up to our newsletter here to ensure you don’t miss a thing.

[1] Companies with more diverse leadership teams report 19% higher innovation revenue – https://www.bcg.com/publications/2018/how-diverse-leadership-teams-boost-innovation

[2] Up until the early 1970s women were denied access to underground mines on the premise that they were “back luck”. However, after lawsuits and investigations of sex discrimination, resolutions were passed, and this superstition was finally put to rest.

[3] Women in Mining survey report 2022 (ausimm.com)

[4] https://www.wgea.gov.au/data-statistics/data-explorer

[5] A similar lack of resonance with the “women in mining” movement was noted by some panellists, who found such initiatives placed them into a gender-based box and did not represent them accurately. However, others have found great comfort and support in these initiatives.

[6] Achievements include Michelle Keegan’s 2023 Space Professional of the Year, Tijana LaBianca appearing in the WIM 100 Global Inspiring Women in Mining 2020, Simone Naicker’s position as a Mining Elites in Africa 2024 and nomination in the 2024 Woman of Stature Awards South Africa, Tess Lewis’s 2021 IGO Leadership award and 2022 Internal Masters Candidate selection, Michelle Ash appearing in the WIM 100 Global Inspiring Women in Mining 2016 and winning the Technology Innovator of the Year Award by Mines and Technology in 2019. There are also many more we have not listed.

[7] https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2023-04/women-mine-of-the-future-australia.pdf