Geopolitics: an inevitable chaos

It’s all a game

Resource security is a global geopolitical game that has been played for centuries. Some play to primarily make money through exports (such as Australia, Canada, Chile, or South Africa) while some play primarily for national security (such as China, the US, India, or Japan). Each plays the game differently, and it depends on their natural endowment, comparative advantage and geopolitical position, and some play on both sides. Country-level strategy and how the “game” will play out matters in understanding the likely focus of investment, trade and ultimately mining innovation of different countries.

“China are the leading thinkers when developing strategies for mining companies. Their perspective comes from that of state-owned companies –they care about the contribution to the country not just to the shareholder”Industry Group Executive

Countries with strategic geopolitical intent, often ascribe a different value in accessing minerals beyond the economics of the orebody itself. These countries are likely to use government-derived influence to either subsidise development or access to strategic orebodies, or to pressure communities and other governments. They will tend to focus innovation efforts more on value chain integration and logistics for example.

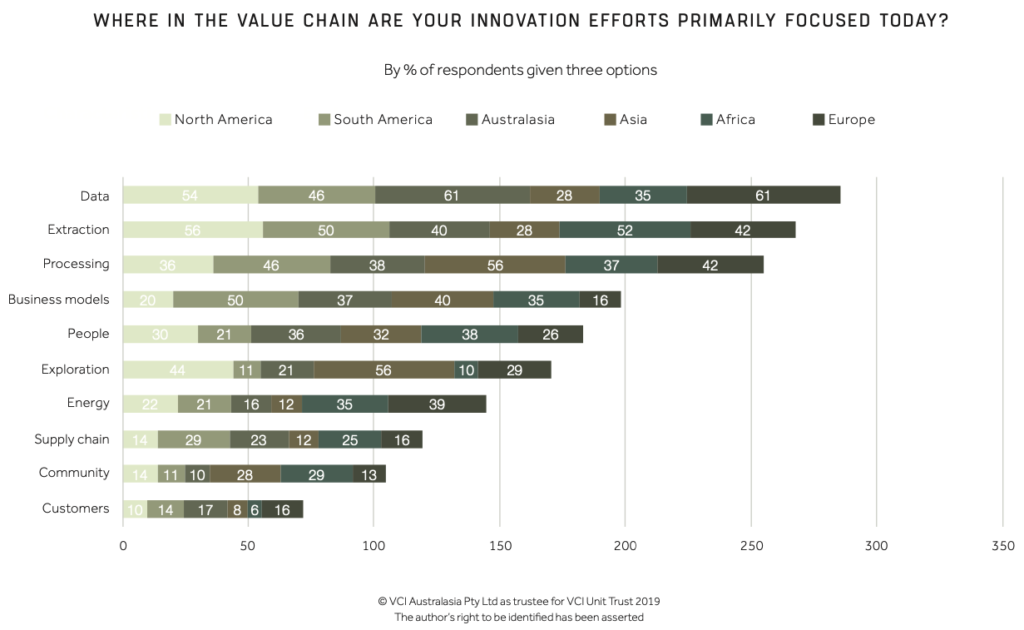

Those with purely project economics at stake often tend to focus innovation more on the aspects which impact project economics (such as extraction, processing, operations). Both are likely to focus innovation on communities, as this is essential to gain access to major orebodies. The major strategic priorities of key mining countries can be classified as follows:

New minerals

This geopolitical game is evident in the global race to develop “new minerals”, namely those in the battery and electronics industry. Given the strategic benefit of developing this technology capability at home, governments are taking an interest in the supply chains for lithium, cobalt and rare earths, among others. These markets are set to be large and are currently growing quickly. For the first time, the major initial demand for a new commodity is not in the old “Western World”, rather coming from the rapidly developing manufacturing sectors in China, Japan and South Korea.

The industries surrounding these commodities are developing at a breathtaking pace. First-movers are scaling rapidly, for example Chinese state-owned lithium producer Ganfeng acquired smaller miners and established long-term partnerships with customers such as Volkswagen. Given the instability of supply of rare earths from China due to political reasons, Japan is looking to develop its own rare earths industry and will look to spur innovation in deep sea mining to access a large deposit that was discovered off its coast in 2018. In addition, a massive amount of Tellurium, an incredibly rare metal vital in the production of solar panels, has been found on the ocean floor off the Canary Islands. These discoveries will continue to drive innovation in deep-sea mining, driven by strategic and economic value.

Other countries like Australia and Chile, who also lead the world in global reserves and production of lithium, are using their world-class mining capability to work with a wide range of global commercial partners. Private actors in these countries are moving quickly, however the speculative nature of these minerals, their complex supply chains and their overall risk profile may leave the development of these new mineral industries to be driven by juniors and start-ups who are less constrained by boards and mainstream investors.

The nature of these minerals as key players in future supply chains means that they have strategic ramifications, high potential, pervasive uncertainty, and complex state-based supply chain dynamics. Therefore, the minerals themselves, and the assets that produce and process them, will be valued differently. In addition to conventional supply and demand analyses and alignment with commodity cycles, investors must value these minerals acknowledging the numerous risks and uncertainties. This includes upside and downside volatility, which are a feature of government intervention and fast-moving shifts in end-use products (e.g. battery technology).

“The big guys are going to get disrupted by other miners in other commodities. They are going to turn around to a half a million-market capitalised company and say, “why don’t we have what they have?” Because they weren’t agile enough”Industry Group Executive

Given the complexity of valuing and trading in these assets, the most successful producers are likely to have strong integration with strategic partners to underpin both capital supply and offtake to mitigate risks. There will be significant innovation around inputs, exploration for more minerals and collaboration between producers and customers. Whether the current crop of minerals remain key to the development of technology and battery industries, or whether new minerals appear, we don’t yet know. What we do know is that the world will be watching.

“We don’t embed political risk in the stochastic modelling as an extra couple of points on a discount rate. A couple of percentage points don’t really account for the potential for protests blockading access to an asset and shutting down production for 6 months. For us, it’s a judgement call”Investment Executive

Who’s got the data?

The interests of states will also matter in the release of governmental data. Artificial intelligence is increasingly capable of analysing massive geographical datasets to compete in the exploration space, and so governments will expect more from companies using this data in the form of royalties, investment and jobs. Data also has a big impact on marketing and investment decision-making, as economic and industrial forecasts, as well as real-time economic and demographic data is key in making critical decisions of investing or divesting, and buying, selling or holding. Privileged access to data, as well as generous government investment in critical services capabilities to beat the competition, could distort the established industry incumbents.

In the case where larger powers view the industry as a global political game to be won, mining companies around the world could be vulnerable to supply chain shocks. This could lead to the development of regional or political blocs, and the exclusion of international investment or operations in certain parts of the world. The risk is obvious, the solution less so.