The need to navigate political and jurisdictional risk is nothing new to the mining industry. Not only do mining companies often operate in high-risk regions, but they are also one of the most heavily regulated sectors in the world. In recent years however, the industry has also been grappling with declining ore grades, depletion of known deposits and increasing demand for critical minerals to fuel the transition to net zero. It is estimated that in the absence of further mine development, the lithium market deficit could reach 700kt by 2030 and the copper market deficit could reach nearly 4.7mt, based on current supply projects.1

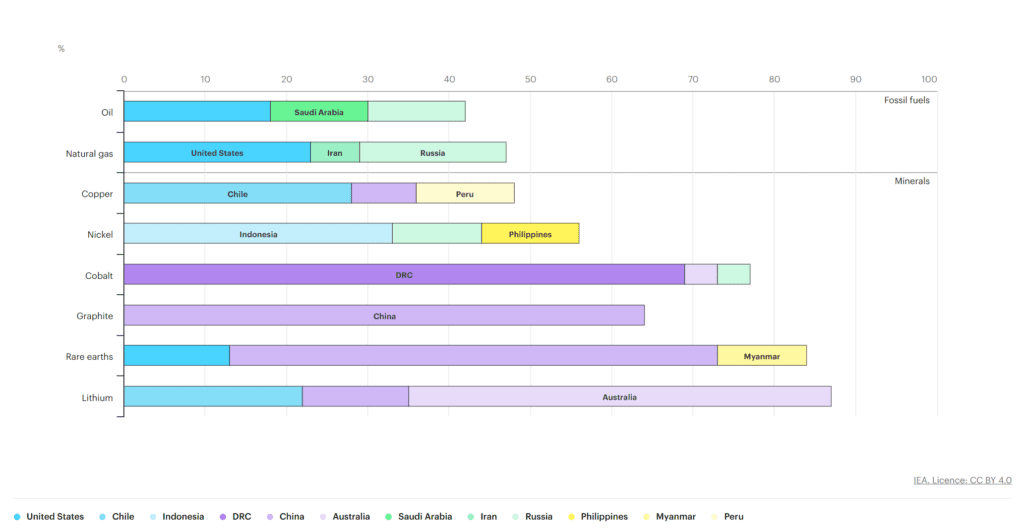

Some of the countries with the highest perceived jurisdictional risks are resource rich. Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has almost 70% of the world’s supply of cobalt, and Indonesia contains over 30% of the world’s nickel supply.

Share of top producing countries in extraction of selected minerals and fossil fuels, 2019

IEA, Share of top producing countries in extraction of selected minerals and fossil fuels, 2019, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/share-of-top-producing-countries-in-extraction-of-selected-minerals-and-fossil-fuels-2019, IEA. Licence: CC BY 4.0

For many mining companies this leads to a complex problem. Do they continue to operate in low jurisdictional risk countries, improving yield in brownfield sites and plunging significant money into greenfields projects hoping to hit the jackpot? Or do they accept having to navigate a higher risk country, for potential large returns?

There are many different forms of jurisdictional risk, stemming from legal, regulatory, or political factors that exist in different regions. Developing countries in particular are usually seen to have vulnerabilities due to due to weak regulatory frameworks, such as poor protection of land rights, unclear approval processes, poor verification of impact assessments and unclear rules for community consultation. Given that licences and approvals are necessary at each stage of the mining process and government often owns relevant land, mining companies are continually having to navigate the political and regulatory landscape. Risk for the mining industry in particular, often manifests in the awarding and/or renunciation of mining licenses.

Recent examples

Most recently, AVZ Minerals has found itself at the centre of attention with its Manono lithium and tin project in the DRC. In May 2022, AVZ Minerals received ministerial decree for the project, touted to be one of the world’s largest lithium deposits.

After receiving the decree and spending millions on resource definition to get the resource ready for development, the DRC government revoked the company’s exploration and mining licenses. AVZ Minerals had reached a $4.6 billion valuation2 last year before a trading halt relating to the mining and exploration rights for the project.

The project is now in limbo. At a time where lithium players across the globe are benefiting from positive pricing environments, AVZ Minerals is facing a potential disaster.

Leo Lithium’s Goulamina Lithium Project is another example of a project navigating the impacts of jurisdictional risk. Located within southern Mali in Africa, the site is one of the largest underdeveloped, high quality spodumene deposits. The project is fully permitted, and likely to come online in the first half of 2024. Despite all of this, the asset was seen to be undervalued throughout 2022 by some, with jurisdictional risks being slated as one of the main reasons. Mali is known for its political instability, military coups, violence, and a lack of transparency.

How to navigate jurisdictional risk

Shareholders are increasingly watchful of exposure to jurisdictional risk, with the demand for transparency higher than ever. Companies are becoming increasingly cognisant of the impact of broader community expectations on them. In the 2021 State of Play: Mining Industry Survey, respondents reported they believed community expectations were going to have one of the biggest impacts on mining over the next 15 years (second only to environmental concerns).

Given a high proportion of undeveloped ore bodies are in developing countries, the mining industry is left with a rather unique situation. Those companies who can operate in vulnerable jurisdictions successfully may create a competitive advantage, whilst those who fail may be locked out of potential high value resources. To navigate jurisdictional risk will require increasing due diligence by companies, heighted compliance procedures, and strong policies. It will also require a sophisticated approach to operations.

New technologies that increase transparency will be a key component to addressing the risk. Blockchain has already proved itself in mining as a transparent trading platform, as it can be used to track a resource’s movement through the stages of the supply chain, from when it’s mined to when it appears in a final product.

There are huge opportunities for companies who are willing to operate in vulnerable jurisdictions. As pressure increases for new supplies of resources critical to the future, companies will be required to undertake significant process and cultural change, oversight, and technology adoption to assist in navigating this risk.

The major considerations and drivers for cybersecurity in mining and the emerging pathways forward.